Rob the Ranter

Newcastle 1861

In 1861 observer and commentator, known only as Rob the Ranter at the time, wrote a series of articles that were published in the Newcastle Chronicle in 1862. The articles describe his sojourn in Newcastle where he had sought the advice of well-known medico Richard Ryther Steer Bowker for an ailment of the lungs. He spent three months in Newcastle during which time he made observations not only of various inhabitants, but of the town itself including the poor state of the roads, his unpleasant experience of touring a coal mine near Newcastle and his return to Cassilis by coach which took days to complete......

Reminiscences of a Three Months' Sojurn in Newcastle and Maitland, By Rob the Ranter.

IT WAS ONE COLD MORNING at early dawn, about the 10th of June, 1861, that I arrived at Newcastle having come a distance of two hundred miles, to get treated for a bronchial disease of the lungs, and an aneurysm of one of the arteries of the right breast by a certain famous, and justly celebrated disciple of Esculapius, who dwelt in that city.

Being a perfect stranger, I had some difficulty at first in procuring suitable lodgings, but at last succeeded in arranging matters at the Prince of Wales Hotel , worthily presided over by "mine host" Lewis Jones. My disease, though not very painful, was of that slow, insidious character, which induces extreme melancholy to gather, with great debility, and prostration both of physical and mental energy ; consequently I had little relish for conversation or society, and seldom mixed with any company, save that which chance or circumstances unavoidably brought me into contact with, at my lodgings. Having nothing to do, I often used to indulge in long rambles, wandering here and there, solitary and alone, in 'melancholy meditative mood,' viewing the scenery and natural curiosities of the city and its environs. Almost every object I beheld was new to me, and on that account interesting, drawing my attention and exciting my admiration, though others passed them by, pronouncing them 'very common,' while the townspeople went a step further, by affirming they were ' nothing at all.'

The reader may feel somewhat surprised that I should see anything in Newcastle so very new and interesting, but his astonishment will cease when I inform him, that this was the first city or seaport town I had seen for a period ranging over twenty-three years, that being the length of time since I had left the Land 0' Cakes, for New South Wales; but being then only about two years old, I had not the least recollection of the embarkation at home, the voyage across the ''saut sea," or the landing at Sydney from the good ship Coromandel, on the 2nd October 1838. From Sydney, we proceeded a distance of two hundred and odd miles into the far interior, inhabited at that time almost exclusively by the wild, untutored aboriginals, and scarcely less uncivilised white convict population, for the most part a rude, illiterate, and in some cases, as equally ferocious a set of beings as the sable races by which they were surrounded.

These "old lags," as they were termed, were never very choice nor instructive in their discourses, which were at all times plentifully garnished with oaths, and generally about bullocks, horses, or sheep ; and when these local subjects became stale or exhausted, they were occasionally varied by the introduction of minute and sickening details of the numerous bacchanalian revels, lewd scenes and exploits they had witnessed, or taken an active part in, both at home and abroad ; and these "yarns" again were interspersed here and there with anecdotes of bushrangers, and the cruel robberies and cold-blooded murders they had perpetrated. Thus reared during the earlier years of my boyhood, amidst, and in almost daily contact with, these rude specimens of humanity, can it be wondered at that I grew up in almost to that ignorance of the great world at large, as well as with the refinement, conventionalities, and usages of genteel society, or that I should be, even now, (though I have since become better acquainted with the world, and with a more refined and intelligent class of associates,) somewhat rude and uncouth in my manner and address, and strangely ignorant on many subjects, on which the well-educated, travelled man of the world is perfectly at home. But though thus brought up, as it were, in an atmosphere of ignorance and moral depravity, I generally contrived to keep myself superior to the greater bulk of those by whom I was surrounded, and though I could not help often witnessing, and being acquainted with many of their vices, I did not practice them. Yet, perhaps, I did not escape altogether scatheless. It is said, custom is second nature, and though I did not imbibe many of their loose principles, yet my early familiarity with their numerous evil practices, may have had the effect of somewhat blunting the finer feelings, and moral sensibilities of my nature, notwithstanding that I exercised a continual and rigid surveillance over myself to prevent their influences.

At an early age I evinced a taste for reading, which, though there were no schools in the bush then, and very few even now, I was partially enabled to gratify - thanks to an affectionate mother and a lady friend, both alas, now no more - who taught me the rudiments of reading and writing. Though often forced by circumstances to associate with worthless characters, whom I could not help despising, I absented myself from them on every possible occasion, and seizing some favourite volume, would plunge into the pathless forests, where, in solitude and silence, my thirsty soul could drink in the streams of knowledge, as they flowed pure and unpolluted from the Storied page, over which I pored. There I made myself acquainted with many of the great and good of different ages; with illustrious heroes, who, not actuated by ambition, or a desire of personal aggrandisement, but by the purest and noblest feelings of humanity, had employed the prowess of their glorious and invincible arms in hurling despots and tyrants from their bloody thrones, and in restoring oppressed, down-trodden, and enslaved nations to liberty, and the enjoyment of freedom and happiness ; and with heroes of a still higher order heroes of the quill - men who had spent their lives, and employed their mighty minds and powerful pens in subverting the reign of Ignorance, and bursting the bonds of Superstition and Prejudice, which had so long bound the human mind in the chains of Error, and in illuminating and improving the benighted understandings of the masses of their own times, nor them alone, for their examples, experiences, and opinions, recorded in books the emanations of their stupendous intellects, and bequeathed to us as legacies, still continue to improve and enlighten our race, and throughout all the succeeding generations of mankind, their beneficial influences will be as lasting as the memories of their authors, which shall only perish when time itself shall be no more.

I trust the indulgent reader will pardon this digression, which has not been dictated by egotism, or a vain desire to give a short autobiographical sketch of my early life, but because it was partially necessary, in order to show that though I had heard and read a good deal, I had little or no actual acquaintance with, the world, excepting that portion of it where I had been reared, or with its curiosities, natural or artificial, or with the numerous and wonderful achievements of modern science and art.

Hence, nearly everything I beheld was novel and interesting to me. The ever-restless ocean, with its shores of rock and sand, its myriads of finny inhabitants disporting themselves in its fathomless depths, and its wavy bosom gemmed with the richly-laden crafts of all nations, bound to every part of the known world ; the busy wharf with its piles of costly merchandise, its gigantic steam-cranes, raising huge trucks containing many tons of coal, and swinging them round with as much case as if they had been mere feathers ; the numerous railways, with their cuttings, tunnellings, and raised ways, their seemingly endless lines of iron rails, laid on transverse sleepers of wood, along which, ever and anon, hurried with arrowy swiftness the smoke-wreathed hissing, puffing engines, drawing their long trains of linked carriages, laden with merchandise and human souls ; the telegraph, with its whitened posts of immense altitude, extending and rising at long intervals through the town, and seeming, when seen through the uncertain gloom of twilight, or the darker shades of night, like huge solitary spectres, or the tall ghosts of some departed race of primeval giants; the telegraph office itself, with its many mystic wires, its, to me, incomprehensible machinery and revolving wheels, its apparently interminable length of perforated tape, continually coiling and uncoiling itself from a refulgent brass cylinder ; the shrewd-looking master going through the routine of his business with the precision, regularity, and, I may add, the immobility of an automaton.

All these, dear reader, and fifty other objects that met my distended visual organs, were perfectly new to me, and therefore, as a natural consequence, could not be otherwise than interesting. Even the very coals that burned and sparkled on the grate, and which, while they diffused light and warmth to the outer man, were generally giving the coup de grace to some culinary preparation, destined to comfort the inner one also, was a commodity I had never seen before, wool being the only kind of fuel I had previously been acquainted with in the bush.

Visit to a Coal Mine

One of my first excursions from Newcastle was a visit to the Tunnel, an extensive coal mine, some three miles distant from the city. I had previously heard so much of this tunnel from bushmen like myself, who had visited it, that I had conceived an insatiable longing to see it, and, as I sallied from the Prince of Wales to meet the coal train in the vicinity of the Pottery, I felt a glow of pleasurable excitement pervading my bosom at the anticipation of having this ultima thule gratified. I had scarcely time to seat myself e'er the whistle sounded, and we shot along at a moderate pace. The road on each side was lined with tastefully built cottages, the residences of the miners and their families. These dwellings were in general surrounded by small, but well laid out, gardens, with a plot in front devoted to the cultivation of flowers and various kinds of exotics, but, unquestionably, the fairest flowers that met my eyes were the miners handsome daughters, as they came to gaze at us from the doors and windows, and displayed a pair of rosy cheeks, and a captivating face, illuminated by a pair of bright, wicked, killing eyes, one glance from which was enough to destroy a poor fellow's peace of mind for a month to come at least.Some half mile or so from the Tunnel the buildings ceased altogether, and the ranges on each side began rapidly to converge, forming a dark, narrow, tortuous ravine, up which the train moved with some difficulty, as the incline was pretty steep. It was a wild, dismal-looking place indeed. The ranges on both sides the ravine were steep and precipitous, covered principally with a thick and almost impenetrable undergrowth of tangled brushwood and wild mountain vine's, broken at intervals with huge chaotic masses of dark, jagged rock, and varied here and there with the appearance of some gigantic monarch of the forest, rearing high its dusky trunk and giant arms, overtopping and looking down on his surrounding brethren of lesser attitude with an air of silent majesty. The farther up we went, the scene grew wilder and wilder, and darker and darker, and it really seemed as if we were approaching the dominions of Old Nick himself. From a huge heap of burning coal or "slack'' rose vast clouds of dun-coloured smoke, wholly intercepting the rays of the sun, or giving them a red, lurid, unnatural appearance, and shrouding and enveloping every object in dim and horrible indistinctness. I must confess I now began to feel rather nervous; vague recollections of various passages in 'Dantes' Inferno,' descriptive of the infernal regions, began to rush wildly through my brain, and on reaching the Tunnel, and seeing some written notice over the entrance I ran forward fully expecting to see the identical inscription which the immortal poet beheld on the portals of Hell :— All hope abandon ye who enter here. However I was agreeably surprised to find it was merely a notice, written by some heavy masculine hand, in cabalistic characters, and in complete defiance of all the known rules of orthography and grammar, and with less respect for the proper position of the capital letters, requesting a meeting of the miners to consider some question relative to the impending strike.

Meeting with one of the Messrs. Patricks, with whom I had some previous acquaintance, and who was about to enter the Tunnel for a load, he kindly volunteered to take me with him, and give me a ride in his little truck, drawn by one horse. I thankfully embraced the friendly offer, and having been provided with a small collier's lamp, resembling in shape a miniature tea-pot, stuck in the ribbon of my hat, I mounted the sooty-like vehicle along with my friend and entered the Tunnel. As we receded from the entrance, the light of day grew fainter and fainter, till finally it disappeared altogether, and everything before and behind us was shrouded in Cimmerian darkness, save the small space immediately around us, which was lighted up with our lamps, whose strong red glare fell on the jagged roof and walls of the Tunnel, from which the moisture exuded in copious streams. The exhalations arising from the damp floors and walls, and the heavy atmosphere, impregnated with the fumes and smoke of burning lamps and blasting powder, thereby producing an efflusive, whose remorseless attack on my olfactory organs quickly dissipated any reminiscences of eau de cologne or scent shops with which I happened to be regaling myself at the time, and soon had a very perceptible and disagreeable effect on my respiratory organs A feeling of sickness, dizziness, and nausea and complete exhaustion seized me, and although I had never fainted in my life, nor seen others in that state, I was afraid I would do so on this occasion, or, perhaps, what was infinitely worse, die altogether, and as the probability of this last occurrence flashed across my mind, a sensation of horror and secret dread took possession of my soul.

I was not one of those who entertained a slavish fear of death, but yet, like many more in this sinful world, I always flattered myself I would be better prepared to die to-morrow than to-day, and the thought of having to shuffle off my mortal coil in this horrid hole, which, dark grim, and dismal, and all as it was, might be a perfect Elysium, when compared with the locality to which I might be assigned in the next world, perfectly annihilated any little amount of moral courage I possessed. To contemplate dying on a bed, seeing and seen by my friends, beneath the blessed light of that Heaven to which I hoped to ascend was cheerless enough, - but to yield up the ghost in a filthy coal waggon, buried in the bowels of the earth, in the subterranean recesses of this miniature hell, shrouded in such pitchy, palpable, darkness. that to use a Paddyism, "I couldn’t be afther seein myshelf doi", was horrible. All and everything appeared to have conspired against me to make me miserable, and as if the interior of my cranium was not painful enough already from the crowd of appalling ideas that were filling it almost to bursting, it was ever and anon receiving an unceremonious bump from some projecting portion of the roof, as from time to time I incautiously raised it, in a vain endeavour to pierce the gloom that surrounded us. bitterly cursing the ill-starred curiosity that had led me hither, and which I need scarcely inform the reader was now more than satisfied, although as yet we had not proceeded more than 200 yards.

I implored Mr Patrick, if he had the slightest grain of tender compassion in his composition, to turn his waggon, and restore me once more to the outer regions of light and liberty, if it were only to die. This he informed me was impossible, as the vehicle ran on rails and could not be turned till it reached the end of the line, but he tried to encourage me by telling me we had only about a quarter of a mile to go now ; after all the agonies, physical and mental, I had endured along the 200 yards which we had as yet traversed, perfectly horrified me, and as to the consoling assurance " that the farther I went I would feel the better, and get used to it ," I thought it somewhat analogous to that administered by a certain hangman to his victim, who, on expressing a dread of the rope, was assured that " though, it moight feel rayther toightish a bit fair the fust kipple o’ minits or so, it wuld be nothin at awl arter that ."

However there was no help for me, and with an involuntary exclamation of " Oh ! dear, this is horrid !'' I summoned what little philosophy I could muster, and with the fortitude of a martyr resigned myself to the evils I could not avoid, and on we sped, preserving a profound and almost, painful silence. Once or twice I became doubtful as to whether I was not actually dead although I was not aware of it, but on trying to force a ' hem ' and a little cough or two, I succeeded, and became convinced of the pleasing fact that I was not defunct yet at all events, but was still in the body. This gave me encouragement, and, as my friend had predicted, I began to feel decidedly better, and get used to the uncongenial atmosphere. With reviving spirits my curiosity returned, and I commenced to examine, as well as the dim light of our lamps and the speed at which we were hurrying would allow, the walls on each side of the passage along which we were going.

The passage we were traversing, and which appeared to be the main one, seemed to be about 12 or 14 foot wide, with two sets of rails laid down, so that two waggons or trucks could conveniently pass each other going in and out. The roof appeared to be principally formed of solid rock, which obviated the necessity of supports, but the walls, except where intersected by veins of rock, were chiefly composed of different layers or seams of coal, varying from three to seven feet in thickness, though in some parts of the mine, I was informed, they are as much as nine feet through and and through. Many millions of tons of coal have been extracted from this mine, and supply seems as inexhaustible as ever. From the sides of the main tunnel numerous smaller ones branch off, penetrating far into the surrounding hills, some of these are exhausted, some in full working order, and others only in a state of formation. (To be continued.) The Newcastle Chronicle and Hunter River District News (NSW : 1859 - 1866) Wed 10 Sep 1862 Page 2

HERE AND THERE we passed a solitary miner, at work in some painful and un-natural position, but mostly on his side, picking away at the ebony mass before him, which he first undermines and then hews down in huge lumps, the larger the better, I believe, so long as they can be handled. They generally arose at our approach, and as the strong glare of our lamps fell on their faces, and brawny frames, perfectly naked as far as the waist, and besmeared and blackened with the dusty particles arising from the mineral they were working, I could almost have fancied them fiends arisen from the lower regions to welcome us to their infernal abodes, had it not been for the expression of cheerfulness and contentment, visible even through the mass of dirt that encrusted their physiognomies, and the good-humoured smile and bow of recognition with which they saluted my friend, and bestowed an enquiring glance on myself. Though most of the miners whom we passed had a sickly and cadaverous appearance, they seemed, with few exceptions, to be healthy, cheerful, and contented. But the laborious occupation they follow, and the unwholesome atmosphere they are forced to breathe, must certainly exercise an un-wholesome influence on their constitutions, and considerably shorten the average duration of their lives.

During the previous week, while warming my shins at the comfortable fire that always blazed in the cheerful lap of the Prince of Wales, I had not the remotest idea that it required so much toil and hardship to procure the sable mass that hissed and crackled in the grate before me. But now that the curtain was raised, and I was somewhat initiated into the mysteries and miseries of a miner's mode of life, I could not help pitying that unfortunate portion of our race, thus immured in a living grave, as it were, and doomed to toil in darkness, solitude, silence, for a scanty pittance, to prolong an existence that can have few pleasures, by raising a substance for the diffusion of light, heat, and happiness, to their more fortunate brethren above them. But I soon found out, however, that my commiseration was thrown away, or, at all events, not appreciated by the objects which had culled it forth, for on reaching the end of the tunnel, and when about to return, I fell into conversation with miner, whose broad accent at once proclaimed him to be a man 'frae ayont the Tweed,' and on remarking that his occupation must be very unhealthy and cheerless, he remarked, " losh blaas ye, mon, nut at; it's a mere naethin when ye're used till't. " On my reiterating my former opinion, and describing the unpleasant sensations I had experienced on first entering, he gazed at me with an incredulous smile and an expression of mingled contempt and surprise, as he answered, " odds, mon, that's wonnerfer, I wad a thocht a muckle buirdly felly like ye, wad nae hae fand onythin like that ; ye maun be unco saft ." On informing my blunt and somewhat uncourteous friend, that my 'softness,' as he was pleased to style it, was the result of disease, and not constitutional, his physiognomy assumed a more sympathising expression, as he replied, " oh; aye, ye're nae weel, are ye, deery me, I didna ken that; naebody tao louk at ye wad jalouse there was onythin the matter wi' ye, but that lung complaint is vera deceivin, an people aft leuk best when they're worst; I suppose Bowker's attendin tae ye, is he ?" On replying in the affirmative, he continued, " eh, mon, that Bowker's a cliver cheil ; he has pit hunners o' people tae richts, that ither damned quacks kid dae nacthin till, excep ease them o' their siller; but Bowker's nane o' ye're purse doctors, it's nae ye're bawbies that he tries tao git at, but ye're disease, and giff he canna pit that awa, whilk is nae often the case, he tells ye jist richt bung off ye're ayont his skill, and that there's nae' use bein at ony mair expense, trying to get rid o' it. But the best thing ye can dae noo is to gang awa hame, and consult ye're Heavenly Physician, and while ye houp for the best, aye tae keep yersel praparit for tae worst. Then syne he jist settles up wi' ye, charging accordin tae yer means, an giff ye hae not the siller jist the noo, he tells ye tae sen it sometime when ye hae it tae spare; indeed, he's a noble man, that Bowker; he has aften and aften been kent tae atten the puir fae naethin, and frae ane end o' New South Wales tae the ither he has nae a match for skill, generosity, an charity, an ivery ither guid quality that maks the doctor, the gentleman, and the Christian ."

By this time, Mr. Patrick had unyoked the horses from the empty truck, and fastened him to the full one, and on informing me all was ready to return, I prepared to bid my new friend and enthusiastic admirer of Dr. Bowker, adieu. At first he had regarded me with contempt, setting me down as some effeminate coxcomb, while I took him to be one of those petulant, sullen, morose individuals, who inflated with a false idea of their own supreme importance, and eaten up with self-esteem, can never find a kind word or pleasant look to bestow on any one but themselves. Now, however, a complete revolution had taken place in our sentiments, and we began to look on each other with feelings akin to those of friendship. Though somewhat rude and uncultivated in his appearance and address; I found that beneath this rough and unprepossessing exterior, he possessed a warm heart and a tolerable stock of common sense, which he had a fearless, free, off-handed way of delivering, in the rich vernacular dialect of his native land.

Appearance of the Streets

Considering the time Newcastle has been in existence, and its importance as a coal-producing district, it was often a matter of surprise to me to notice the miserable appearance of the streets, and the primitive and unpretending style of most of the buildings. Occasionally, an edifice with some few claims to architectural beauty is met with, but its effect in general is spoiled by the contiguity of a collection of hovels, styled, par excellence, 'little shops', that would certainly disgrace any shepherd's hut and not a few of those merry-make haste erected bush tenements, yelept "gunyahs or bandicoots.' which I have beheld amidst the pastoral wilds of the Castlereagh.The greater part of the thoroughfares along the streets are in an execrable condition, being wholly unpaved, and in a state of nature, Hunter street excepted. But even the improvements in this street, as I was given to understand, are nearly all of recent origin, having only been commenced since the city's incorporation into a municipality, some four years ago, when Mr. Hannell was elected mayor, an office he has continued to hold ever since, with credit to his constituants, and honour to himself, and under whose able and energetic management the town has made wonderful advances. Since I was down, now some six months ago, I understand extensive improvements have been going on in Bolton and Church-streets, and several others, and are now in an advanced state. But at the time I was there, they were in a fearful condition, being intersected by numerous gullies, deep creeks. holes, and ruts, all standing temptingly open, and ready at all times to receive into their affectionate embraces any luckless benighted stranger, or hapless wight absorbed in unconscious reverie, who was unfortunate enough to approach too near their precincts, quickly restoring him to a consciousness of the materiality of his existence, and his present whereabouts, and in some cases presenting him with a broken limb, a sprained ankle, or some equally tangible proof of the deep sense they entertained of this condescending visit. In the absence of holes, ruts, &c, the streets were graced here and there with large pyramidal heaps of the most beautiful white sand, into which you sink ankle deep at every step, with the most delightful ease, and without the slightest effort on your part. In hot, dry weather, a walk among these embryo sandhills was particularly delightful, for great quantities of the fine penetrating sand immediately found its way into your boots, by which your feet were quickly ornamented with sundry gigantic blisters, while your spotless stockings were soon metamorphosed from their prestive snowy whiteness, into quite an opposite colour, being tinted in the most lovely and variegated manner, with numerous black and whity brown spots, and all, too, without employing the aid, or incurring the expense of the dyer's art.

But these were not the only pleasures to which you were treated during your peregrinations through these delectable localities; for if old Boreas was any way boisterous, great clouds of dust were raised the finer particles of which, without the least apology, hesitation, or ceremony, insinuated themselves into your eyes, mouth, nose, and, in fact, every imaginable crevice they could find about your person, compelling you, though you were the most adamantine-hearted creature in the world, to shed tears of real feeling, and producing at the same time the most exquisite tickling sensations in the upper part of your throat, thereby causing you to cough, though wholly free from any pulmonary disease, and to expectorate a liquid, or perhaps it would be more appropriate to say, substance, whose colour and consistence would not suffer any disparagement by a comparison with Stockholm tar.

In the very centre of some of the streets in the lower grounds, were large pools of stagnant water, in some instances coated over with a refreshing green scum, the fruitful source of malarious exhalations, and extremely beneficial to those residing in the vicinity, who happened to entertain suicidal notions, as it completely obviated the necessity of laying violent hands on themselves, or of going to the expense of purchasing strychnine, prussic acid, pistols, hemp, &c., to bring about the desired ultimatum. But as I have slated in a former paragraph, these streets have undergone great repairs, since I saw them last, and many improvements are, I believe, still in progress; but it will take years of toil, and an immense amount of capital and labour, before ever they can assume a thoroughly respectable appearance, owing to the natural difficulties to be contended against.

The City

The city is principally built along the top, sides, and foot of a hill at the embouchure of the Hunter River into the sea, which is covered in many places with large, soft, yielding beds of sand, which are continually shifting with the winds, or being cut up with floods, consequent on heavy rains. There is a telegraph office and a railway station in Newcastle, and as this was the first time I had beheld either of these wonders of modern invention, they excited my curiosity, and I was never tired of watching them. I generally used to contrive to be at the railway terminus on the arrival and departure of every train, examining the exterior of the engine, with its short, refulgent brass funnel, puffing forth volumes of light coloured smoke or steam, and noting the various specimens of humanity all intent on some little business or affair of their own, as they alighted from, or ascended the different carriages, and committed themselves to the care of the steam horse, who in a few minutes sped away whistling, snorting, and puffing, at the rate of twenty, or twenty-five miles an hour.The Telegraph Office

I often used to loiter about the telegraph office, observing the master manipulating the wires, and transmitting with a face of the utmost unconcern, messages as various in their imports, as they were almost countless in their numbers. But though amused, I was not instructed, for the mysterious process of transmitting and receiving messages remained, and still remains as great a secret to me as ever. The electric telegraph is certainly a great boon to mankind, and its invention conferred incalculable benefits upon his species, when he discovered it, and brought it into operation. Yet I can never gaze on this unconscious messenger of joy and woe to thousands, without having a train of reflections, all more or less tinged with melancholy, awakened, perhaps, while I am gazing on it. It is transmitting money to the needy, filling their hearts with gladness, and enabling them to supply their wants at once, and to assume a respectable appearance in society; though, in some instances, it only furnishes them with the means of indulging their depraved appetites, and plunging into various excesses, which not only tend to their temporal and eternal ruin, but soon exhausts those funds which their friends sent (though perhaps, they could ill afford them), at their entreaties and representations of being in deep distress.Or it may be enabling the up-country merchant to communicate instantaneously with his town agent, instructing him to take advantage of the depressed state of the markets to purchase goods at half their value. If he succeeds, his employer will rejoice, never for one moment reflecting that his gains are another man's loss, — that the unhappy vendor of these articles, pressed by hard circumstances and remorseless creditors, was thus forced to part with his goods at a nominal value, in the vain hope of delaying, not averting, the resistless advance of gaunt poverty and grim want, who were fast enveloping himself and his affairs in irretrievable ruin, and who at the very time the purchaser of his effects is exulting over his cheap bargains and anticipated profits, may be wandering about the streets penniless, homeless, and miserable, maddened perhaps by the consciousness that he is not alone in his misfortunes, and that a fond wife and helpless family, who can neither work nor want, are looking up to him for that support he is expected, but is not able, to afford them.

Or perhaps some condemned criminal, whose guilt though established is not without many extenuating and mitigating circumstances, is about to be executed ; and with failing heart and tottering limbs, that almost refuse to bear his weight, is on his way to the scaffold. Visions of brighter days float before his eyes, when he was young, innocent, and happy, dwelling in a cheerful home, lit up by the smiles of love — perchance in a far distant land — surrounded by affectionate parents, noble-hearted, manly brothers, bright-faced, sunny-eyed, guileless sisters, and those who had not only called but had proved themselves friends.

The Newcastle Chronicle and Hunter River District News (NSW : 1859 - 1866) Wed 17 Sep 1862 Page 3

PERCHANCE TOO, THERE ARISES BEFORE THE EYES of his imagination the well-remembered image of some fair, fond maiden, whom he had known and loved in earlier and happier days, but whom he can never hope to see again ; for these scenes are past — past— for ever gone, and can never return again— no, not even in dreams, for the fiat of his fate has gone forth, and his life is about to close in ignominy and dishonour, amidst the execrations of his fellow-creatures Far, far from those kind, those early friends, who, could they be present, would still love the man while despising his crimes — mourn over his faults, his chequered career, and ill-fated end — and in after years, when himself and his crimes were alike forgotten by the world, wander by his lonely tomb " full oft when dewy eve " began to shroud the earth in gathering shades of gloom, inspiring sombre, melancholy thoughts — calling up holy feelings, and awakening recollections of the past— and there, while gazing on the little grass-grown heap that contained his remains, and reflecting on all he had been and all he was now, moisten his dis-honoured ashes with the tears of pity and regret. As these wild, maddening thoughts whirl tumultuously through his brain, his soul melts — the fountain of his feelings, which may have been closed for years, open, and the large, hot, scalding tears course each other down his rugged cheeks. He attempts to raise his blood-stained hands to brush them away, but in vain — these hands are bound, never to be loosed until he is no more. Perhaps he is approaching the scaffold— has ascended the steps — and, on reaching the platform, casts a furtive glance on the assembled crowds below, but no sympathising faces meet his eyes — no kind words of consolation, commiseration, or hope salute his ears — and with a sickened and heavy heart he turns away to join in the prayers breathed for his forgiveness be- fore the throne of grace by those holy men who have attended him throughout his confinement, and now accompany him to the confines of another world. Now, perhaps, the executioner is proceeding to adjust the fatal rope — his heart beats fast, and his breath, which he imagines is about to be stopped for ever, comes slow and thick. Already he imagines himself trembling on the verge of eternity — about to be ushered into that unknown world which millions have entered before him, and through whose portals all earth's succeeding generations must follow, there to have all the doubts and fears which have distracted his mind regarding the probability of a future state of existence finally set at rest, and the grand secret of- "to be or not to be" revealed to him, and his eternal state of absolute joy or misery for ever fixed. He expects that in a few moments more that part of himself which now is so busily thinking, will be torn from its dearly-loved tenement of clay, where it has resided so long in security — but whose evil passions and wicked desires have brought about its present misery, and will perhaps be the cause of its eternal ruin — and be winging its flight with, as yet, untried pinions through an unknown world, inhabited by myriads of disembodied spirits, on its way to the judgment seat of an offended but righteous God, there to give an account of the deeds done in the body, whether they were good, or whether they were evil. As these thoughts rush wildly with lightning speed through his brain, appalled reason totters on her throne, and a sensation of dizziness and blindness comes over him as he casts a long, last, vacant, fading glance around him on that world which is about to pass from his sight for ever, and — but a clatter of iron-shod hoofs is heard in the distance — an indistinct murmur runs through the gathered crowd as a rider is seen urging his foam-covered courser towards the fatal platform — all eyes turn on him, for he is a messenger from the telegraph office, bearing the prisoner's reprieve. The Executive have taken his case into consideration, and, on account of the many mitigating circumstances in his favour, have pardoned him. Were there no telegraph the reprieve would arrive too late — the unfortunate culprit would be beyond the reach of their clemency. But there is a telegraph — his life is spared, and and he hears with a thrill of joy never to be forgotten the glad tidings that he is pardoned on earth, and rescued from the very jaws of death, and maybe of hell, to be restored once more to the regions of life and liberty.

Or, may be at this very moment that serpentine wire that stretches its quiet length along from post to post, is transmitting along its unconscious surface the intelligence to fond and anxious parents that their child — perhaps a son, and an only one — has just met with some horrible and fatal accident, by which he has been hurled in one instant from the stage of time into eternity — perhaps, alas, in an wholly unprepared state for that "great and last change," and has been consigned a mangled and mutilated corpse to the silent keeping of that dust from whence he sprang. Oh, awful and unexpected catastrophe? Who shall picture the agony and grief of his sorrow-stricken parents, thus bereaved of their nearest and only pledge of reciprocal affection just as he was emerging from boy into manhood— of him whom they had fondly hoped would have been the prop and comfort of their declining years — would have watched beside their couch of sickness, soothed by his kind words and presence their last hours on earth, closed their dying eyes, and, at last, when death had severed "the union between the soul and the body," have accompanied their remains to that "last, long home appointed for all living." On him depended their sole and only hope of having their ancient name rescued from oblivion, and transmitted to posterity, and therefore for him they vainly hoped and anticipated a long and brilliant future and when, at last, "like a shock of corn fully ripe," death claimed him for his own, a translation from time into eternity under more favourable and happier auspices than it had pleased the all wise disposer of events, in the inscrutable dispensations of his providence, to award him as his lot. Vain hopes ! — sad realisation of the truth of the Scriptural adage. " Ye know not what a day may bring forth."

Or, may be a message of a far different character — of a far more joyous import — is at this moment winging its' silent flight along yon elevated wire, from which the tiny denizens of the air have just arisen wi'h a flutter of alarm. Perhaps some fond, absent lover is transmitting a message to that fair being whose graceful manners, handsome face, and witching smile have won his heart, assuring her of the unaltered state of his affections, and informing her when she may expect to see him, or, mayhap, still better, when to prepare and hold herself in readiness 'or that long-looked-for, come-at-last day when he will lead her blushing, trembling, and fluttering with nine hundred and ninety- nine little nameless emotions to the hymenial altar, there to undergo that interesting ceremony which will link them together in the indissoluble bands of matrimony, and make them as one through life "either for better or for worse.''

Or, may be — but conjectures would be endless, for various as they are numerous, are the messages that daily and hourly vibrate along that attenuated continuity of galvanised wire, whose thickness scarcely exceeds a quarter of an inch. Oh, wondrous and variously useful vehicle of intelligence, destined at no distant day to encircle the globe in thy embrace, bringing the ends of the earth into instant communication with each other, and thereby enabling relations and friends, hindered by many a sea shore, to converse with each other, as it were, face to face, and enquire after one another's health and welfare.

The Wharf

I often used to saunter down to the wharf to gaze on the various and numerous vessels as they shot in and out of the harbour, or lay surging lazily about on its calm surface, fastened to their anchors. At the time to which I allude, which was just previous to the 'strike,' the bason of the Hunter was literally crowded with vessels ; and never having seen so much shipping before — at least, to recollect it — it was some time before I could divest myself of the impression, as I gazed for the first time on their gigantic masts, towering their huge lengths far up into the air, that I was not beholding some ancient forest of decayed pines, and that the partially clewed-up sails, as they dangled and flapped from the crosstrees, were not pieces of mouldering bark hanging from their gnarled and knotted arms. It was some time before I could distinguish one kind of craft from another; and indeed I scarcely know whether I would have ever been able to tell a ship from a schooner, or a schooner from a cutter, had it not been for the untiring instructions of a seafaring gentleman named Mr. Walker, who, like myself, was only a sojourner in Newcastle, having been forced to leave his vessel on account, of something being the matter with one of his hands, which, however, at the time I knew him, was nearly well. He was a well educated and intelligent man— a shrewd observer of human character, and one who had travelled and seen a good deal ; and from his society I derived much pleasure, it not profit. He attached himself greatly to me during our brief acquaintance, though what he could possibly see about me to interest him so much in my behalf I am at a loss to conceive. At that time, as I have already observed at the beginning of these ' reminiscences,' a morbid melancholy was preying on my soul — I was suffering both from physical and mental debility, and my cranium was about as destitute of ideas as a block of wood.Mr. Walker was constant and strenuous in his endeavours to banish this hypochondriac tendency, by striving to make me forget the cause of it, and hurrying me from one scene to another. He often used to take me in fine weather for a walk on the top of the hill, and being somewhat of a botanist, with a slight knowledge of geology also, he used to point out the different species of plants to me, telling their names and describing their various properties ; and when we came to a seam of coal cropping out at the edge of the cliffs, he would forthwith commence a dissertation on its probable origin from the decayed matter and debris of ancient and primeval forests. To convince me that his theory was correct, he would commence detaching portions of the sable mineral, and then inserting his knife between the layers, separate them, showing the prints and, in some instances, leaves themselves in a high state of preservation, together with the impress of plants, twigs, and brunches of trees, which had been imbedded there centuries ago, and had helped to augment the general mass. I was delighted and amused with his lively and instructive discourse, which was never monotonous, tedious, or insipid. I often made fruitless attempts to join in it, but was so fearfully dull and phlegmatic that it was a perfect burden for me even to think, much more speak ; and generally the only reward my friend received for his exertions to entertain me, was a faint smile, a slight inclination of the head, or a solitary "Humph," which I succeeded in articulating at long intervals through my olfactory orifices. I often wondered he did not tire of my un-interesting society, but he did not; on the contrary, his friendship seemed to increase, and was always of that unobtrusive, dis-interested and unaffected kind that neither exacts nor seems to seek a return. But the dearest and best of friends must part. Mr. Walker's means would not allow him to re main too long idle; he engaged as mate with the master of a vessel bound for Melbourne, and on going on board we indulged in a long, hearty shake of the hands, and parted-may be for ever.

After Mr. Walker's departure, I often used to indulge in long, lonely rambles along the precipitous cliffs that line the shore to the eastward of Newcastle, where, seating myself on some prominent and jagged knoll, I would loiter for hours gazing on the vast ocean below, watching the restless, untiring waves, as with relentless, giant sweep they careered madly towards the rocky shore, up whose jagged sides they leapt, like imprisoned monsters thinly striving to burst the bonds which permitted the sight, but not the enjoyment, of liberty, but, like them, baffled, broken, and scattered, they recoiled in wide-spread showers of angry foam into the seething depths below, to be succeeded by others, gain and again in endless succession, only to meet the same fate. "No inapt illustration," I would murmur to myself, " of the way in which the fairest hopes and brightest prospects of us poor short-sighted mortals are often dashed, wrecked, and for ever broken on the reefs of disappointment, and we are flung back into the sea of despair, where, like some rudderless vessel, we are driven hither and thither by the storms of furious and conflicting passions, till at length, overwhelmed beneath the waves of misfortune, wearied, dispirited, and exhausted with our fruitless struggles. we resign ourselves to the irresistible current of adverse circumstances, which hurry us on and on through the breakers of sickness and pain till ultimately our frail barks of clay are dashed on the rocks of death, and we sink to rise no more beneath the silent ocean of eternity. We are but little missed — perhaps regretted — and, ere long, our very names are forgotten. Others soon fill our vacant places — these run the same race that we have ran, meet the same fate, and, finally like us, sink into the cold shades of oblivion, to be succeeded by others, and these again by others in long succession, till time shall merge in eternity, and this terrestrial ball be wrapt, in the devouring flames of the last conflagration.

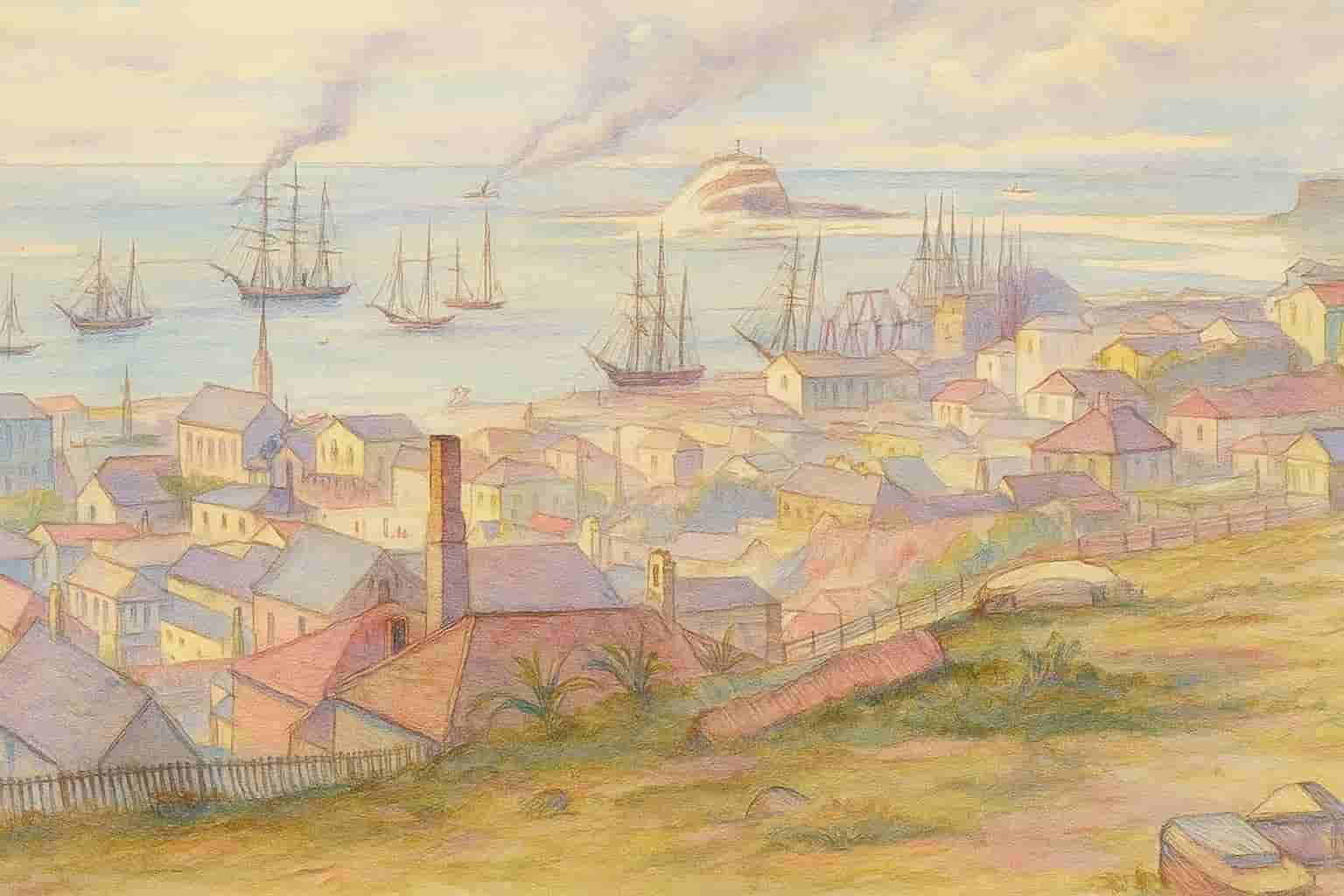

Image: AI Created Image from 'Port of Newcastle' - Australian Town and Country Journal Sat 10 Feb 1872

Farther out, beyond the range of the breakers, the sea was generally studded with sailing vessels and steamers of various sizes and dimensions; and as the former with their snowy, distended sails shot hither and thither, as if instinct with life, obedient to the helm, they really seemed like winged, airy spirits of a higher and brighter world ; while it required but a very little stretch of the imagination to convert the latter — with their brown, dingy, and sooty appearance, and their gaunt funnels towering high into the air, shooting forth vast columns of dun-coloured smoke, which hung long, wavy, serpent- like trains in their wakes — into emblems, in miniature, of the infernal regions, and the cries and shouts of the captains and passengers, distorted and rendered indistinct by the distance, into the howls and wailings of the damned.

At the time I was in Newcastle there was only one newspaper, the "Newcastle Chronicle" published twice a week. On a perusal of its columns I soon ascertained the city was not without its local literary celebrities, both in upper walks of prose, as well as in the flowery paths of poetry. Among the most conspicuous followers of the 'muses' were three individuals, using the respective initials of "D. F." " D. A. R." and M. E H. The latter was a female, and as I have never had the pleasure of seeing a real bona fide poetess, I conceived a longing desire to make her acquaintance, or at all events to have the supreme felicity of seeing her — which latter desire, after many unavailing efforts and adventures was partially gratified — but of that anon.

I soon ascertained who D.F and D. A. R. were, and was not long in making the first mentioned gentleman's acquaintance, whom I found to be well educated, and possessed of considerable talent and literary ability. He was the very beu ideal of a poet, having a head graced with thickly clustering curls of raven hair, eyes intensely dark and brilliant, a prepossessing intelligent countenance, and a handsome well formed person, but like many other men of genius, he knelt rather often at the shrine of Bacchus, and was a leetle too assiduous in his attentions to the bottle, a feeling that often reduced him to a state of absolute impetusosity, from which, however, phoenixlike, he always rose again by his own exertions. I never had the honour of speaking to D. A. R. which I ascertained to be a ship carpenter, and a hardworking man, residing on the North Shore, who employed his leisure hours, after the toils of the day were over, in the cultivation of letters and poetry. But though denied the pleasure of conversing with him, I had the happiness of seeing him several times hammering away with chisel and mullet, at the sides of some vessel requiring repairs, and I have sat, or reclined for hours on the wharf, watching him, without, however, his appearing to be aware of the keen scrutiny his physiognomy and cerebral developments were undergoing. Every time I saw him he appeared to be absorbed in deep meditation, and then suddenly rise it upwards as if thinking some inspiring duty for some boon vouchsafed in the shape of a brilliant idea, or invoking the assistance of the 'celestial ulno' to enable him to add an other couplet to his already portentous "Lay" written in humble imitation of "Marmion," a poem from the pen of the immortal Sir Walter Scott. "

As I am neither inclined nor gratified for, I will not say what opinion I did, or do entertain of this production, which it is to be regretted he did not furnish; but I may observe en passant that though, somewhat hyperbolical, rude and uncouth in its construction, and rather harsh, and unharmonious in the flow of its versification— it was not without its merits, literary and moral, written as it was with the design of exposing the local abuses, and current evils of the day, The best proof that some such exposure (though written in a more candid, and inviting style, and with a little more regard to the "The Governor's visit to the Hunter " Lay after Marmion" sacredness of private' and family feeling) was needed, and that he has succeeded in hitting many a 'right nail on the head' was the torrents of abuse that were burled against him by the enraged victims of his cutting satires ; indeed so incensed was one worthy manufacturer of the 'time of day,' whose other occupation, (represented by three golden coloured spherical globules) had been mercilessly attracted and opposed in one part of the ' lay,' that un-able to regulate his own temper, he forsook for a while, his workshop for his study, and seizing his pen became the author of a few vedicatory stanzas, which he doubtless intended for poetry, but whose inimitable construction, it is earnestly to be hoped both for the sake of his veracity as a gentleman, and his reputation, and success as a tradesman were not emblematical of the internal organisation of those 'clucks and vatches,' which he was continually holding forth to his customers, ' were de ver besht in de coloonas, and more betterish and sheaper dan you wot boye dem in London, or Sydney .' (To be continued.) . The Newcastle Chronicle and Hunter River District News (NSW : 1859 - 1866) Wed 24 Sep 1862 Page 3

Poor D.A.R., the only reward he was doomed to receive in return for his literary labours, were the loud murmurs and execrations of his numerous foes, while the timid few who approved, and therefore should have applauded, were silent, because they feared the multitude. About this time also, he attacked Miss M.E.H., in one or two of his poetical effusions, but was ably answered by that lady herself, and D.F., whose gallantry prompted him to take up the gauntlet in her defence.

As I have previously observed, I had conceived an ardent desire to see this M.E.H., who, I was informed, resided with her parents, in the vicinity of Lake Macquarie Road. But this was no easy task, as I was a perfect stranger to her, and had not the slightest acquaintance with her relations, or in fact anyone connected with her. Her father being a blacksmith, a worthy son of Vulcan, I often regretted that I was not a miner or a carrier, so that I could have feigned an excuse to call and get my pick sharpened, or my axletree laid, but I was neither. Had I been an Apollo or an Adonis, endowed with heavenly proportions and godlike features, I might have entertained hopes that she, in company with other romantic nymphs, might have been attracted to the windows, to cast a languishing and admiring glance at the majestic stranger, and thus unwittingly have afforded me an opportunity of having a peep, en passant, at her. But though neither a monster nor a satyr, I was not possessed of sufficient vanity to imagine myself handsome enough for that, so I must depend on some other means to bring about the desired consummation.

At length, chance accomplished what neither foresight nor stratagem could, achieve. One day I happened to be sauntering by the place, when, to my joyful surprise, I saw that be- sides the blacksmith's forge, they kept a little shop and a suburban post-office. Here then was an opening I had little expected, and of which I determined to avail myself of at once. Of course, everybody is allowed to call at or go into a post-office, to enquire about letters without exciting suspicion, for the master or mistress is not sup- posed to know whether he expects such things or not. To tell the truth, I had little hopes of getting a letter here, but was not altogether sure, but if there was such a thing, I felt sanguine I would have an opportunity of 'knocking down two birds with one stone,' as the old saving has it ; for I would not only get my epistle, but stand a good chance of seeing the lovely poetess herself behind the counter. I was not long in stopping across the street, and noticing a list of unclaimed letters, I cast my eye down the column of S's, but thought I failed to discover my patronymic amongst them. I determined to go and enquire.

Accordingly I proceeded to the door, and in thrusting in my head, beheld to my infinite chagrin and disappointment, no Miss M. E. H., but her venerable mother busily engaged plying her needle. I would then have made a precipitate retreat, but it was too late, so smoothing down my features a bit, and giving a 'hem' or two, — (bless my heart, what useful things these ' hems' are ; if it were not for them, and the pocket handkerchief with which we blow and wipe our noses, when they require neither, I do not know what we would do when we become embarrassed or nervous, or break down in our discourses from want of ideas, or suitable language to convey them; or meet with a friend, and are at a loss what to commence talking about) ; I proceeded to exchange the usual salutations of the day with her, and ended by enquiring if there were any letters there for Mr. ---- , telling her my name. After a moment's reflection, she replied, she did not think there were, but she would not trust her memory, but look. After inspecting the address of five or six (all that were in the box); she continued, there are none for you to-day, Mr. — — , but there may be some to-morrow. 'Ugh !'' I muttered in a tone of disappointment that required little dis- simulation, ' it can't be helped, good day,' and strode away down the street towards my lodgings. Happening to pass that way in a few days again, I resolved to make another call, not without a faint hope that I would be more successful this time than last. " Faint heart never won fair lady," I mentally ejaculated, "so here goes to try my luck again," I was destined to be dis- appointed again, for there stood Mrs. H. before me, instead of her gifted daughter. On enquiring about letter, she recollected me at once exclaiming in her usual bland and courteous manner, 'oh, you are the gentleman that was here the other day ; I don't know whether there are any letters for you or not., but I will look.' Her search was as fruitless as before, and not wishing to put her to all this trouble for nothing, I asked her to let me have half-a-pound of lozenges. ' Very well,' she replied, ' but I am very busy just now, but my daughter' will attend to you ;' Mary,' cried she, raising her voice, 'come here and serve this gentleman.’ Gracious heavens ! I could scarcely believe my ears ; was it possible ; was I dreaming, or was I really awake ; was I actually about to have my long cherished wish gratified by seeing what I had never seen before — a real living poetess — I could scarcely believe it, or realise my position; and how ever I managed to stand on my feet, or keep from describing a pirouette high into the air, and hitting my head against the ceiling; or upon uttering a wild stentorian shout, in the exuberance of joy, I cannot tell to this day.

A wild, tumultuous gush of delight thrilled through my frame, my heart throbbed with pleasure, and vibrated from one side of my bosom to the other, like the pendulum of an American clock. In a few moments, M.E.H. herself stood before me in propria personia, and at once came up to the ideal I had formed of her. Though not exactly a Venus nor a Madonna in appearance, she possessed a graceful figure, and a handsome, intelligent, though somewhat pale countenance, gemmed by a pair of intensely dark, deep set eyes, lit up with the fire of genius, and extremely expressive. It is well for me that I was not destined to be long exposed to their witching influence ; for if I had, I shudder to think what might have been the consequences, the least of which would probably have been an inflammation of the heart, which would have set the skill of the justly celebrated Dr. Bowker, and the all-potent remedial powers of Holloway’s ointment and pills, alike at defiance, and could have only been allayed by an emollient fomentation of warmly-breathed ' yes's,' or a soothing decoction of kind words, expressed from the cherry lips of the fair being who had caused it. She was wholly unconscious that she was an object of notice, and appeared to be in as great a hurry as her mother, and proceeded at once to ask me what kind of lollies she could have the pleasure of serving me to. I pointed mechanically, though I must confess without looking in the same direction, to a shelf I had previously noticed, and answered, ' these kind, if you please, Miss.' In a few moments she had the requisite quantity weighed, and wrapping them in a piece of paper, handed them to me, and received the change with a polite curtsey, and soft 'thank you, sir.' Being total strangers, of course our conversation was somewhat constrained and embarrassed, and extended little beyond a few common-place remarks about that useful and exhaustless topic, the weather, and the recent, disastrous floods in Maitland, &c. Having now received all I had asked for, I could not consistently with the rules of etiquette stay any longer, and therefore was reluctantly forced to bid her good bye; and this was the first, last, and only time, I had the pleasure of seeing and conversing with a poetess.

Ladies of Newcastle

During my peregrinations about Newcastle, I was 'often struck with surprise, at the almost total absence of those dandified coxcombs, or lady-killers, so many of whom are generally to be seen in other towns strutting about with an air of great importance, as if they really belonged to some superior race,' and almost spurning to touch that dust from which they sprang. Their bodies dressed out bon ton, loaded with jewellery and ornaments, and their heads, devoid of 'sense' but not ' scents,' groaning beneath a weight of powder and pomatum, as if to make up for the great lack of mental calibre within, gazing from time to time on their gaudily dressed figures, which they imagine to be the very ne plus ultra of earthly perfection — the focus of general attraction, and the envy and admiration of the fair sex.The greater portion of the Newcastle male population appeared to be a comely, vigorous, hard-working, and industrious race, who neither sought nor eat 'the bread of idleness’ and I must pay the female portion the compliment of saying I never recollect to have seen so many really handsome women in any other town or city which I have visited. I will not say they were "angelic creatures all," but the generality of those whom I saw had full, well rounded, voluptuous forms, faultless features, long flowing tresses of dark shining hair, and clear, brilliant, love-speaking eyes, one glance from which was enough to fire the heart of a misanthrope. It is really an enigma to myself, however, that visceral concretion in my left breast, yelept a heart, managed to escape scatheless.

I was always a worshipper of female loveliness, especially when that outward loveliness was only an emanation of the beauties within, and so susceptible of the 'tender passion,' that one bright melting glance from a pair of dark languishing eyes, owned by some fair member of the feminine gender, was always, sufficient to set my. heart on flame, as easily as a lucifer match is ignited by being rubbed on a piece of sand paper. This predilection for the society of the fair, often got me into awkward scrapes, and adventures with the worthy hostesses where I happened to be lodging; for if there was such a thing as a kitchen in the vicinity, illuminated by the presence of some fair cook, laundress, or chambermaid, I was sure to be there on every possible occasion, to the infinite chagrin and dismay of the worthy landlady, who would declare "she would rather be without that S.'s pound a-week, than with it, for he was always in the kitchen, and there never was a ha'porth done while he was there," and the no less discomfort and ill-concealed uneasiness

Of that young signing swain, whose heart Had felt the force of Cupid's dart;

And now with all its hopes 'and pains, Was held in love's subduing chains,

By that cook-maid with eyes so bright, Who laugh'd and sang from morn till night!

Who strived at once, with woman's art,

To please the stomach and the heart;

And while she bak'd, and boil'd, and fried away,

Could still find time to kiss and play.

But who not having the same firm hold of hers, dreaded the approach of a rival, lest he might supplant him in her affections — an occurrence which, if it took place, would, he vowed, "have such han heffect on im, that hit would bruk is art, and koze im to coot is throat wad a razur, han commit sewerside hor some hothor horful krime."

It was in vain, for the hostess to request me politely just to be kind enough to make myself scarce; I invariably answered with an air of assumed and ludicrous gravity, "oh yes, directly madam." But as these ‘directlys' generally occupied about an hour, her patience often became exhausted, and in she would rush like an enraged Niobe' with an uplifted broom-handle of awe- inspiring length and weight, which she would proceed to lay about me in such a lusty manner, that I was forced to make an exit, rather more hasty the honorable, being convinced "in less than no time," that "discretion was the better part of valour."

Departure from Newcastle

The time now drew nigh when I must take my departure. I was greatly improved in health and appearance, and at least two stone heavier than when I came down; but, notwithstanding this, my medical attendant gave me very little hope of ultimate recovery. He told me to hope for the best, but, at the same time, to be prepared for the worst; for though I might live tolerably easy for a number of years, my disease was almost certain to prove fatal in the end, and take me off very suddenly, He had known, he said, a few solitary instances in which people suffering from my complaint had partially recovered, and he hoped I would add one more to the number.I had arrived in Newcastle about the beginning of June, and it was now about the middle of September, and I had stayed longer than I had intended to do, and spent more money than my limited means would well afford. During my short stay, averse and all as I had been to join in society, I had formed several lasting friendships and associations, which I could not think of without a pang of regret. I would fain have stayed altogether, but it might not be. So having bade my other acquaintances farewell, I called my worthy host, Mr. Lewis Jones, from whom I had experienced great kindness, to bid him good-bye. He had always predicted from the first that I would recover, declaring that I was not half so bad as I thought I was. He now wished me increased health, a successful journey, and safe arrival home to the rural shades of D______, on the Castlereagh River, and ended by extending his hand, to which I gave a warm shake, and hurried from the house.

I was accompanied down to the railway-station by a fellow-lodger, a man in the service of the corporation, whose herculean proportions had procured for him the soubriquets of "Big Bill." He was a worthy son of "Ould Ireland," and a true and faithful type of his free, open- hearted generous countrymen ; and I had enjoyed many a pleasant ramble in his company during his peregrinations through various parts of the city in quest of some damaged road, or obstructed drain, which required the application of the "spade" he carried over his broad shoulders, "jist to titivate it off a bit, and make it look decent and party." On passing Mr. E. L. Cooke's "Metropolitan Hotel," we went in to have a parting glass together, and forthwith proceeded to drink each other's healths in what my friend pronounced to be " a good glass of fust- rate rum." We then proceeded to the railway-station, and bidding him, adieu, and receiving a parting grip that made me doubtful whether I would ever have the use of my hand again, I flung myself into the first carriage I came to, which was fast filling with a picturesque and motley group of passengers.

Ere many minutes, the doors of the carriages were closed and locked, and the shrill whistle--- the signal for departure --- having been sounded, we sped away towards Maitland at a rapid rate. As we receded swiftly from the old city "spread o'er hill and vale," I cast a long, lingering look behind, and as my eyes wandered from one well-known object to another, and the thought intruded itself that this might be my farewell look, and that I was now perhaps beholding these familiar objects for the last time, I could not repress an involuntary sigh of regret. At length the distance and a curve in the line hid the city from my view, and settling myself back in my seat, I became absorbed in deep reverie, and for a while was wholly oblivious of the present. Before long, most of the passengers gathered into little groups, and began conversing on various topics, all more or less lively and interesting, although I noticed one or two reserved, melancholy individuals, like myself, who preferred sitting aloof from the rest, and communing with their own thoughts.

Hexham

At Hexham the greater part of them alighted, and we were joined by a fresh passenger--- and elderly individual, and really one of the pleasantest old gentlemen I ever recollect to have come across. His whole face was wreathed in one broad smile, and the very wrinkles in his forehead seemed to be laughing and poking fun at each other. His good humour was contagious--- there was no resisting it--- and, in spite of myself, I was drawn into an animated conversation about the ruinous results of the late strikes, the calamitous effects of the Maitland floods, the prospects and probable yield of the forthcoming harvest, and, in fact, twenty other topics, all more or less interesting--- but for which, under ordinary circumstances- I would not have given "no that spittle out over my Baird," nor thought of, but for him, and smiled and laughed heartier than I had done for months past. It was really a pleasure to be in the old gentleman's company, and the time passed merrily away till we reached the West Maitland station. Here I determined to alight, although I had taken my ticket for Lochinvar, as I thought some of my acquaintances from the bush might be down witnessing the trial of the notorious Black Harry, and a case of horse-stealing which was tried about the same time; and if there was, I would have the pleasure of their company home, and perhaps get a lift on some of their spare horses or other modes of conveyance, when once we got beyond the boundaries traversed by the mail coaches, which was a distance of sixty miles from home, all which distance I would be under the necessity of travelling on foot should I not succeed in our chasing or borrowing a horse, or sending home for one.The old gentleman, who, by the way, was a farmer residing near Maitland, alighted at the same time as I did, and insisted that I should accompany him to the nearest hotel for the purpose of having a farewell glass--- an invitation which, not being over abstemious, I at once accepted. Instead of having one each, we had two, which soon warmed the old gentleman's heart, and made him, if possible, more hilarious and hearty than ever. He declared I was the best companion ever he had travelled with, and insisted that I should accompany him home, where his wife and daughters would be only too happy to receive me and make me comfortable for the night. I thanked the old farmer heartily for his kind offer, but assured him I was extremely sorry my time would not permit me to avail myself of his hospitality, and extended my hand to him to bid him adieu; he caught it with the grip of a vice, as if determined to leave an impression of his friendship upon it, and gave it such a hearty shake that I began to entertain serious doubts that he would dislocate my shoulder. The Newcastle Chronicle and Hunter River District News (NSW : 1859 - 1866) Wed 1 Oct 1862 Page 2

Maitland

LEAVING MY FARMER FRIEND, I sauntered leisurely, carpet bag in hand, down High street, Maitland, casting a cautious but searching glance from beneath the well-pressed-down leaf of my cabbagetree on every one whom I met, in hopes of seeing someone whom I know, but in vain, and I had almost began to despair, when a rather tall figure, clad in bush habiliments, standing at the door of Mr. Arken's Hotel caught my view. On drawing nearer I was agreeably surprised to find he was a person with whom I had some previous acquaintance, but whom had little expectation of seeing in Maitland. He told me he was thinking about buying a spring cart, and if I had time to wait he would give me a lift up in it, and even if he did not purchase a cart he said he would be able to assist me as he had a spare horse about 60 miles on the road, and if I thought proper to wait till he was ready to start, we could take the mail to where the horses were, and thence ride home.This was a piece of kindness I did not expect from him, for though we had been acquainted for some time, I cannot say our friendship increased with an equal ratio, but on the contrary our intercourse had only served to inspire each with a feeling towards the other, bordering on contempt. But I must confess I was partly to blame for this, for about -two years ago, in one 'of my lighter moments I had immortalized the herculean 'proportions of nose, which was the most conspicuous facial ornament he had, in ten or twelve stanzas, which were not very flattering to his' personal vanity. However, in the excitement of meeting in a strange place, these old feelings were forgotten, and we entered the hotel together to have something to cheer the inner man. Here I questioned my acquaintance farther as to when he purposed starting, to which he replied ' In about three or four' days.' On hinting that I feared that would be too long for me, as I was not overburdened with a redundancy of cash, he exclaimed in rough but expressive bush phrase, 'Oh ! never mind that my young buck, I'll stand to you like a darned brick. I have a little ' tin ' left yet, and While I can raise the 'dust ' you shan't go short . Here, he continued, pulling several notes out of his pocket, ' take these and be hanged to' you, but mind its not everybody would give you so much after making a song about his nose .' 'Oh! thank you,' I stammered out, overpowered by his generous' offer, though short, I am not exactly destitute of the needful and have as much I think, if used with economy, as will take me home, but, nevertheless, I am as grateful for your friendly offer, as, if I had accepted it.' Indeed his unexpected kindness and undeserved, generosity quite overcame me, and I felt heartily sorry and ashamed for ever 'having allowed' my love for the ridiculous to overcome' my better sense so far as to hold up the poor fellow's nasal protuberance to obloquy. However he gave me no time for apologies, but proposed a walk up the town. He said it was not every day he came to Maitland and he intended to make the most of it while there, and have a ' regular good spree.' This was a declaration he had little need to make, for his shining face, dilated eyes, ludicrous expression of countenance, coupled with a most tremendous heightening of the point of his proboscis, so much so, indeed, as to give me the most unspeakable concern, lest some short sighted smoker would mistake it for a coal of fire, and go to light his pipe at it, told me more plainly than words could, that whatever he might be going to do, he had already been pretty constant in his devotions to the shrine of Bacchus. The Newcastle Chronicle and Hunter River District News (NSW : 1859 - 1866) View title info Wed 8 Oct 1862 Page 3

THAT EVENING WE STROLLED INTO THE OLYMPIC THEATRE to witness the performances of Harry Houdini, the great and renowned(for so the play bills had it) poly national singer and actor. But though this was the largest , theatre ever I had been in, I cannot say I thought much either of the singing or acting, and amused myself more by scrutinizing the audience than the actors, who were every now and then greeted with loud and long thunders of applause, but for what reason I was at a loss to conjecture, and could not help thinking that the audience before me, however respectable they might be, were not altogether unlike some idle packs of the canine race which I had seen, who, when one of their number gave a bark at something he had seen the day before, immediately followed suite and commenced yelping and howling at— they knew not what --but just because they heard the other dog do it.

At length feeling wearied and slightly indisposed, I sought out my friend, and proposed returning to our lodgings, but as he did not feel inclined to leave just then, but promised to follow in the course of an hour or two, I went home without him. On reaching my hotel I requested the landlord to show me a sleeping room with two beds, so that when my friend returned he could have the spare one and we would be together in the morning. To this proposition Boniface at once assented, and leading the way up a flight of winding stairs, which seemed almost endless, ushered me into a neat little dormitory, where, ensconcing myself between the snowy sheets, I very soon fell into the embraces of Morpheus, and did not awake till next morning about sunrise.

On opening my eyes and looking around, I espied a tenant in the opposite bed, which I at once concluded to be my friend, and having arisen and attired myself, I went over and gave him a rather unceremonious shake, exclaiming, ' Come, my hearty, it is sunrise, get up. For early to bed and early to rise, Makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.' But guess, dear reader, what was my surprise, horror, and confusion, when instead of seeing my friend's good humoured, smoothly-shaved, lantern-jawed features, emerging from beneath the bed clothes, I beheld the enraged snubb visage of a total stranger, clothed with a most ferocious looking beard, which had evidently never undergone a sensorial operation since it had first began to germinate, and whose portentious length might have vied with the hirsute honours enjoyed by the celebrated Rip Van Winkle himself. He demanded in a gruff voice what I meant by shaking him that way, and on telling him the mis- impression which I laboured under, and respectfully craving his pardon for disturbing him, he muttered an angry and discontented ' ugh !' and said, ' for two pins he would get up and apply his feet in such a vigorous manner to my lateral extremities, as would teach me to be more cautious in future. This insulting retort somewhat nettled me, and thrusting my face almost into his, I requested him in a tone of mock politeness, not to tear his shirt, nor fly into a passion, for kicking was a game two could play, and that in my opinion it would take a better man than him to do what he threatened, although it was to be behind my back. To this he made no answer, though I could see his eyes flash fire, his countenance reathe, and his lips become compressed with passion as he turned over in the bed, and forthwith commenced scratching his head with such vigour as to leave no doubt whatever in my mind, but that the comfort of that bulbous member of his anatomical structure would be considerably augmented by the use of a small- tooth comb, or a little unctuous preparation which Boby Burns facetiously terms 'fall red hot smeddum.'