William Grant Broughton

First Anglican Bishop in Australia - Diary of a Voyage to Australia

William Grant Broughton was appointed Archdeacon of New South Wales in 1828. He sailed with his wife Sarah and daughters Mary Phoebe and Emily on the convict ship John in 1829.

Following is an extract from a ship-board diary kept while on the voyage to Australia

William Broughton accepted his appointment as Archdeacon of New South Wales with reluctance.[1] His poignant words recorded in his diary when he first arrived in the colony in September 1829 underline his personal struggle to come to terms with all he had left behind....

......The prospect of being soon delivered from a state of irksome confinement occasions no sensation of joy: where we are going there are none of those whom we desire to see or whom we have been accustomed to love and value.

Although he returned to England, his one wish, to be buried at Hartley Wespall, Hampshire, the birthplace of all his children, and where the remains of his beloved and ever regretted boy were buried, was not to be. He died in 1853 at the London home of Lady Gipps and was buried at Canterbury Cathedral.

Ship board diary from the voyage of the John to Australia in 1829

Following is an extract from William Grant Broughton, Bishop of Australia, with some account of the earliest Australian Clergy by F.T. Whittington 1936 consisting of the on board diary kept by William Grant Broughton on his voyage to Australia in 1829 on the John................"There is preserved in the Diocesan Registry at Sydney the original diary kept by Archdeacon Broughton from the time he sailed from England until he landed in New South Wales. Some extracts from this historic record will show how cheerless were the surroundings of the Archdeacon and his party as they journeyed to their new home.

Embarking at Sheerness

The diary begins :'Tuesday May 26th 1829 - I embarked from Sheerness on board the John transport, 440 tons with my wife, our two children, and Samuel and Hannah Hatton, our servants. The ship was commanded by Mr Robert Norsworthy; and had on board 185 (*188) male convicts, besides a crew of 32 men and boys, and about 30 soldiers (detachments of various regiments) under the command of Lieut. Forbes, 89th Regt. Mr Love, surgeon R.N., had the medical superintendence of the prisoners.

Our embarkation was delayed several days by the prevalence of a very strong gale from the N.E. which had little abated when we left the shore. By the kindness of Vice-Admiral Sir Bryan Martin, Comptroller of the Navy, we were furnished with a large six-oared cutter belonging to the dock yard, which conveyed us safely to the vessel at the Little Nore though the swell of the sea rendered the operation somewhat formidable. Such indeed was the state of the weather that two steam packets, one bound to Margate and the other the King of the Netherlands to Ostend, finding it impracticable to proceed beyond the Nore, ran into Sheerness Harbour, where we left them.

We had not been a quarter of an hour on board the John before we were all affected with sea-sickness; and we retired to our first night's repose dispirited and uncomfortable.

Departure

May 27th. At high water this morning we weighed anchor and were under sail by about half past seven: The operations attendant on this manoeuvre would, I have no doubt, be interesting in a well- appointed ship, and with a crew of able seamen. But the crew of our vessel were apparently without experience or concert many of them ignorant even of the meaning of the orders that were issued while the crowded state of the decks, the sight of the prisoners in chains, and of the soldiers loitering about, neither able or willing to render assistance, rendered our departure a scene of tumult and confusion. Our pilot did not spare his reproaches, but he understood his trade, and expressed himself well satisfied with the performance of the ship itself. The wind was about E.N.E. and our progress consequently slow. We came to an anchor in the afternoon opposite a mark on the Essex coast, which the seamen called 'Black Tail Beacon.'In the night the wind blew with much fury, and the motion of the ship was very distressing. Our Captain during the day had been speaking of the danger of losing an anchor and cable and being obliged to put back, which I know had happened to several vessels the day before. There was, I believe, no real danger, but knowing that we were surrounded on all sides by sands and shallows, I could not help considering, as I lay awake, what I might expect my sentence to be if it should please Almighty God this very night to require my soul. My mind was tranquil; and I was in consequence somewhat dissatisfied with myself; being distrustful whether it might not be the effect of insensibility rather than the fruit of a true faith and a well grounded hope.

May 28th. At high water this morning we again weighed anchor. The wind still E.N.E and boisterous. It was nearly 2 o'clock before we passed the North Foreland. As we ran along the coast, I had distant views of Herne Bay, Reculver, Margate and Ramsgate, places with which I had been familiar since infancy. Indeed had the nature of the land allowed it, there was nothing in the actual distance to prevent our seeing the towers of Canterbury Cathedral, beneath the shade of which my early years were passed, and within whose venerable walls I was united to the dear and excellent wife who is my companion and comforter in this voyage. In the Downs our pilot left us; and we proceeded rapidly before the breeze, which was now favourable. The view of Dover with its town castle, cliffs and shipping in the Roads, seen under a bright afternoon sun, was truly magnificent, more so, I believe, than anything I had ever seen. We soon came in sight of and as soon passed by Dungeness Light house. It is either built of brick or is coloured red, which renders it a very conspicuous object in the setting sun. As long as it remained visible, I kept my eyes fixed upon it, and when it at last disappeared in the waves, felt very acutely the taking leave of a country in which I had both enjoyed and suffered very much; and in which we left many dear friends and connections.

May 29th. We had a rapid run during the night, having passed by the coast of Hampshire, the birthplace of all my children, and where the remains of our beloved and ever regretted boy are buried at our sweet Hartley; where if it please God, and should be possible, I would wish to rest by him. In the morning we were between St Aldate's Head and the Race of Portland, and we had hopes of speedily clearing the Channel. Here, however, the wind died away and our progress was at an end. The surface of the sea became smooth as glass. The steersman lashed the helm fast, leaving the ship to her own discretion. I cannot say to the mercy of the winds and waves; for there were neither. There was how ever a continual bubbling swell from below, just sufficient to give the ship a see-saw motion which we felt to be most distressing.

May 30th. The calm continued all night; and a very miserable night we passed. Independently of the motion of the ship, the noises which accompany this state of wearisome inaction are truly harrowing to the feelings, and destructive of repose. Through the live long night it appeared as if every particular board, spar and rope was endued with the faculty of creaking, cracking, croaking and groaning; and the complication of sounds produced, is indeed 'he variety of wretchedness.'

Punishment of a Convict

This day John Hunt, one of the prisoners, having been found guilty of striking the officer of the watch was sentenced to be kept in handcuffs, and to receive three dozen lashes. I was happy in being able to intercede for the remission of the latter portion of his punishment. He is, I fear, a confirmed rogue as this, I am informed, is the second conviction he has suffered, and he is in consequence transported for life. However, my purpose was by this beginning to shew the prisoners I felt an interest for them, and thus to acquire an influence which may be turned to better purposes.Description of a Convict Ship

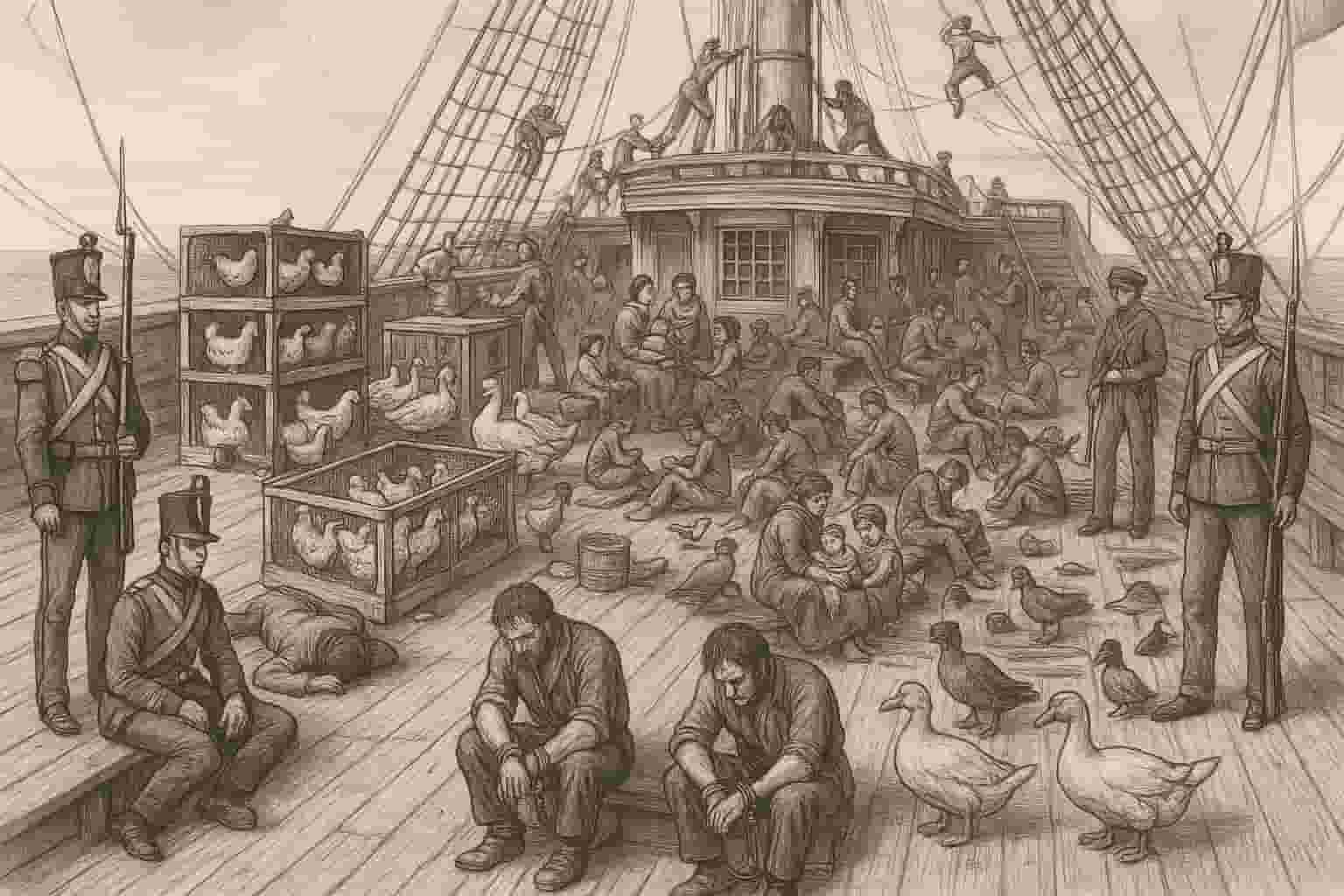

Under date 12 June, while the John was in the grip of a dead calm, Broughton's entry is:I will take advantage of this interval to describe a convict ship....... On each side of the poop, as well as in front of the binnacle, we have coops containing fowls, ducks, and guinea hens, and abaft the cuddy sky-light is a large pen filled with ducks and geese. The intermediate spaces are occupied by sailors refitting yards and sails, and in the front are four privates and a corporal on guard with their loaded muskets lying near. Below on the quarter deck, opposite to each other, are two unhappy wights, convicts afresh convicted of having towed their clothes alongside for the purpose of washing and suffered them to go adrift, which on the score of cleanliness, as they embarked with only two changes of linen each, is much to be lamented. For this offence they are set in handcuffs and fetters and condemned to twenty-four hours bread and water.

About the deck lie the soldiers off guard, some asleep, others employed in various occupations. Two sentries with drawn bayonets parade the deck. From the barricade which goes athwart the ship just afore the mainmast to the forecastle, the prisoners are situated, some sitting idle on the spars and spare booms, others cooking, washing, walking or sleeping as inclination leads. They appear neither discontented, dejected, nor sullen, and are in general very far from noisy. In their behaviour I find them universally respectful, though their characters are in general very unfavourable, most of them having been more than once or even twice convicted and sentenced. Add to this four or five women belonging to the soldiers and intermingled with them, the crying of a child or two, the quacking of ducks, cackling of geese and fowls, and the harsh grating cry of the guinea hens and you will have a fairly complete picture of all that is to be seen and heard on board of a convict ship.

September. 7-10. Fresh breezes, afterwards more moderate and cloudy with rain. No occurrence worthy of notice; but the expected termination of our voyage occasions us some anxiety. But I know not how it is, separation from friends and country have so entirely exhausted our feelings that we have none left apparently to be excited by whatever event. The prospect of being soon delivered from a state of irksome confinement occasions no sensation of joy: where we are going there are none of those whom we desire to see or whom we have been accustomed to love and value. In all this country there is but one person whom I have ever seen before, and that only once or twice as a new acquaintance within the last few months.

Jervis Bay

September 12. The land about Jervis Bay was this day visible, W. about four leagues. Its appearance is inhospitable and the only enlivening appearance is that of numerous columns of smoke arising at intervals along the shore which seem to declare that we are approaching the habitations of men once again though perhaps they be not of civilised kind.At half past 8 this evening as we were drinking tea the chief officer came down to report the welcome news that we had made the beacon light which is at the entrance of Port Jackson. I went upon deck in the hope of also seeing this gratifying sight but my eyes could not reach it though some more practised in observation professed that they could see it appearing and disappearing at intervals. Not being able to sleep through the multitude of thoughts which crowded upon my mind I rose soon after midnight and looked towards the direction of the land. To my surprise we had neared it so much during the last few hours that I could accurately distinguish its long outline until it faded away in the distant darkness. We were now nearly abreast the South Head on which the light-house stands. The light is revolving, exceedingly regular, bright and steady. I looked at it a long time with a kind of mysterious feeling of wonder and thankfulness. It seemed to be the first friend to welcome us to land and to assure us that the perils of our voyage are concluded. The situation is lofty and commanding and seems to imply that the people of the country to which this light is guiding us are capable of making great attempts and of succeeding in them. What an advance is this upon the conception and performances of the savage who not more than forty years ago perchance had his resting place upon that very spot.

Port Jackson

September 13th. This morning we were at the entrance of the Heads but the wind first blew directly out of the harbour's mouth, and then fell to a dead calm. We see a small boat now and then passing to and fro within the port, but they pay no attention to us, and the pilot has not come off, though his station is immediately opposite to where we are lying. We have full leisure therefore to examine the frontiers of our appointed land of sojourn, disturbed only by the apprehension that as there is not a breath of wind and a strong swell sets upon the shore we may have some difficulty in keeping the ship off the rocks if the calm continues, the water being so deep as to render it almost impossible to anchor. The cliffs are lofty, composed of yellow sandstone, with very deep weather stains, and the foliage and herbage which grow upon them appear stunted in growth and gloomy in colour. But for the light-house tower, which is of stone, arid some adjacent white buildings scattered up and down the rock, the appearance of the whole would be dreary and cheerless.A little before eleven the pilot came on board, and took charge of the ship, with which however he can as yet do nothing. Apprehending that in the event of a breeze springing up there would be great interruption to the service on deck through the working of the ship, I assembled my congregation below for the first time during the voyage and preached from St Matthew vii, 13, endeavouring to make my sermon impressive to them, as being the last I should deliver, and our arrival and approaching separation effectual to awaken serious thoughts. God grant my purpose may in some degree at least be answered. As the service proceeded I perceived that the ship was making way through the water and the bustle heard from time to time on deck proved that the pilot was exercising his skill to bring us into port. On returning to the deck I was nevertheless surprised at the rapid progress we had made. A favourable breeze sprang up I was told, shortly before noon, when we entered the Heads. We had now the town of Sydney directly before us, towards which we continued to steer, and at half past cast anchor in Port Jackson opposite to Sydney Cove 108 days after our departure from Sheerness. '

So forty years after the founding of the colony its second archdeacon, in his forty-first year, arrived to superintend the Church's work. It may well be imagined that as they sailed up the beautiful harbour of Sydney his heart, and his brave wife's, must have been wellnigh overcome by the strangeness of their new environment. They had left pleasant surroundings and many relations and friends in the Home land, and Broughton seemed to have laid the foundation of what promised to be a prominent career. Now they had come to a country still in its infancy, without many of the comforts of civilization and, worse than all, with by far the largest part of its population made up of outlaws from civilized soil. Fortunately for themselves, and especially so in regard to the task to which he had given himself, the new archdeacon and his wife were not of those who look back, though the Archdeacon could not forbear from confiding to the concluding entries in his diary an expression of an intense sense of loneliness and anxiety as the ship approached Sydney.

But no trace of depression was allowed to creep into the letter in which he, only a few days after landing, reported to his mother some of the earliest incidents of their Australian life: - He writes:

You will be happy to hear of our having arrived through God’s good providence in perfect health and safety at this our destination. We left Sheerness, as you are aware, on the 27th of May, and we arrived off the 'Heads, 'Port Jackson, early on Sunday, September 13th, 1829. We had therefore been at sea 108 days, and after leaving the Lizard we saw no more land during whole interval excepting what was said to be the island of Palma , at 30 miles distant (which I should have taken for a cloud) and a distant view for a few hours of the coast of Van Diemen's Land the Sunday before our arrival here.

I had written a long account of our voyage, meaning to forward it by any ship we might fall in with bound to Europe. But strange to say we never had an opportunity, not having seen more than three vessels, within any moderate distance during all the passage, and those all outward bound. I write by the present opportunity which is the first that has offered, although the ship is going a circuitous course and not direct to England, since there is a possible chance of you getting this letter sooner than you would do if I waited for another ship going direct to England. In the meantime I will only say that our voyage was neither much better nor much worse than voyages in general go. We had fine weather for nine weeks and a most prosperous passage to the Cape of Good Hope, but during the whole of the subsequent time I was very unwell and uncomfortable, after that the weather broke up and continued to be tempestuous all the rest of the way.

We had a good captain, a very steady respectable surgeon, and a gentlemanly officer of the guard, and they were all of them particularly kind to the children. The convicts in general behaved well and gave very little trouble, but I think soldiers very much in the way on board ship, and our crew was a very bad one. Sally and the children bore the voyage better than I did, though all were occasionally sea-sick.

Sydney Town

We found every one prepared to receive us with the greatest possible attention, and we had not been an hour at anchor before Colonel Dumaresq, the Governor's aide-de-camp and brother-in , law, came to congratulate us and brought a present of fruit, vegetables, eggs, new bread, and fresh butter none of which we had tasted for six weeks before. We found also an invitation from the Archdeacon to come to his house, and on the following day (Monday) we came here where we now are, and have been entertained by him in a most friendly and gratifying manner.I have engaged a house for a year only. We do not much like it, but there is no other to be had. The house is large and roomy enough though badly arranged, but the approach to it is rather difficult and there is no garden but a little miserable enclosure that is more like a sand pit. However we had no choice, and it was necessary we should have a place for our furniture, which we found all safely arrived and apparently not at all damaged, and we hope to take possession by the end of this week. In the course of a year we may meet with something we like better. The house has one recommendation that of commanding the finest possible view of the grand sheet of water which you saw in the panorama, and indeed! from a much more favourable point than was shown in that picture.

On the Wednesday after we came on shore I went, by myself, on board again in order to make my public landing. I had the Governor's barge, and the instant I set foot on shore there was a discharge of cannon from the forts (which for my own I would much rather have dispensed with) and I was received by the colonels of the regiments and their staffs, the Judges, Law officers, members of the councils, and all the first people of the colony. We went in procession to Government House where after my patent had been read, I was sworn into office by the Governor."

OBITUARY OF WILLIAM GRANT BROUGHTON

William Grant Broughton died on 20 February 1853 -

Dr. Broughton was born in 1782, and was the eldest son of Grant Broughton, esq. He was educated at the King's School, Canterbury, and for some years was a clerk in the Treasury; but feeling a strong desire for the ministry of the Church he went to Cambridge, and entered holy orders in 1818. Serving as curate of the parish of Hartley Wespall, near Strathfieldsaye, he attracted the notice of the Duke of Wellington, who appointed him Chaplain of the Tower, and soon after offered him the Archdeaconry of New South Wales, then vacant by the resignation of Archdeacon Hobbs Scott.

Mr. Broughton felt bound to take the offer into consideration, although he would have been contented to remain in his position as chaplain to the Tower and curate of Farnham. He first consulted his diocesan, Dr. Sumner, Bishop of Winchester, as to his acceptance of the archdeaconry. But, as he has himself mentioned, ' it was at the holy table in Farnham Church, that he made up his determination to undertake the office;' for it was there given him to feel that the colonists and aborigines of Australia needed to be fed with 'the bread of life' as much as the parishioners of Farnham. He therefore proceeded to Strathfieldsaye, and informed the Duke that he considered it his duty to accept the archdeaconry. His Grace observed to him that in his judgment it was impossible to foresee the extent and importance of the Australasian colonies, and, he added, 'they must have a Church.' The Duke added, 'I don't desire so speedy a determination. If in my profession, indeed, a man is desired to go to-morrow morning to the other side of the world, it is better he should go to-morrow, or not at all.'

Under these strong influences the appointment was accepted. Archdeacon Broughton accordingly sailed for New South Wales, and engaged in the duties of his office, his jurisdiction extending over the whole of Australia, Van Diemen's Land, and the adjoining islands. It is impossible to conceive more arduous duties than those which fell to the lot of the Archdeacon in these new colonies. He visited all the settlements in these latitudes connected with his archdeaconry, and endeavoured to excite the settlers and the Government to the erection of churches and schools, giving his attention also to the preparation of a grammar of the language spoken by the aborigines, and taking the primary steps for their conversion to Christianity.

In his Charge delivered 13th of February, 1834, he announced his intention of returning to England to make known the religious wants of the colony, being satisfied, having attentively examined and considered all circumstances connected with the advancement of religion, that they were attempting to provide for its general extension and establishment with utterly inadequate means.

To England he accordingly returned in 1835. The first result of that journey was the establishment of a bishopric in Australia, to the superintendence of which he was consecrated on 14th of February, 1836; and, as a necessary consequence, a new archdeaconry was formed for Van Diemen's Land, to which the Bishop collated the Rev. W. Hutching. Other duties than those properly ecclesiastical attach to the spiritual head of a new settlement, and not the least arduous of these relate to the education of the colonists. The question led to infinite controversy; but ultimately the labours of the Bishop for insuring a Church education to children of the Church were, on the whole, successful.

His attention, however, was speedily directed to the visitation of his extensive diocese, and in the succeeding years, as also at later periods, he visited, for the purposes of confirmation and ordination, New Zealand, Van Diemen's Land, Norfolk Island, and Port Philip, as well as the settlements in the colony of New South Wales.

In 1837 the Bishop determined on the erection of his cathedral; much progress has been made, though by slow steps, in the completion of the sacred edifice. In 1841 Dr. Selwyn was consecrated Bishop of New Zealand, and the Bishop of Australia was released from the superintendence of those islands, over which, although not strictly within the limits of his diocese, he had hitherto extended his supervision, visiting them at the end of the year 1838.

In 1843 the diocese of Tasmania was separated from the see of Australia, and Dr. Nixon consecrated bishop thereof. Still the diocese of Bishop Broughton continued of an immense extent, and his visitations and confirmation tours occupied considerable time and labour. In 1843 the Pope sent forth to Australia an archbishop of Sydney, of his own appointment This called forth a well-timed and noble protest from the rightful Bishop of Australia, which was de livered by the Bishop, standing at the altar in the Church of St. James the Apostle, in the presence of his clergy personally attending and assisting at the celebration of divine service, at the conclusion of the Nicene Creed.

In 1848 the bishoprics of Adelaide, Melbourne, and Newcastle were also formed from the bishopric of Australia; and Dr. Broughton having been constituted Metropolitan of Australasia, with the three above-mentioned bishops, and the Bishops of New Zealand and Tasmania as his suffragans, took the title of Bishop of Sydney, instead of that of Bishop of Australia.

The bishopric of Adelaide was endowed by a noble Christian lady (Miss Burdett Coutts); but Bishop Broughton gave up 600/. per annum, out of a stipend of 2000/., towards the endowment of Newcastle and Melbourne, and offered to surrender another 5OOl. if necessary.

In the autumn of 1850 the Bishop received, as Metropolitan and Primate of the Australasian Church, a visit from his suffragans the Bishops of New Zealand, Tasmania, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Newcastle, when, in solemn conference, their Lordships determined to form the Australasian Board of Missions for the conversion of the aborigines in their respective dioceses, and the propagation of the gospel among the unconverted islanders of the Pacific Ocean. They also agreed to certain rules of practice and ecclesiastical order, which they recommended to the attention of the clergy and laity under their jurisdiction. They also resolved upon the necessity of duly-constituted provincial and diocesan synods; an important movement, which led to much discussion in the British Parliament.

For the advancement of this great object the Bishop sailed again for England, choosing, with characteristic energy, the novel route across the Pacific Ocean, the Isthmus of Panama, and a voyage across the Atlantic. His Lordship arrived in England from St. Thomas's, by the La Plata (known as the fever ship), in November last. His noble conduct in administering the consolations of religion to the dying captain and others, fearless of any personal harm, and how he remained on board after the vessel had arrived at Southampton until every invalid had been landed, and the dead buried by him, has merited the approbation of all who have read the accounts in the public papers. After the fatigue attending such a journey, and the fearful incidents of the voyage from the West Indies, his Lordship suffered severely in health, but soon recovered sufficiently to visit his venerable mother in Warwickshire, and to spend a few days with other friends.

At the January meeting of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, the Bishop of Sydney occupied the chair, supported by the Bishops of Antigua and Capetown; and having, through the Archdeacon of Middlesex, received the congratulations of the Society, he delivered an interesting address, which is given in the Ecclesiastical Gazette for Jan. 11, 1853. On Friday, 21st of January, at a meeting of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, the Bishop of London presiding, he received an address from that venerable Society, which, together with his admirable reply, is inserted in the Colonial Church Chronicle for February.

He afterwards delivered the first sermon at the reopening of Lambeth Church, on the 1st of February; attended a missionary meeting at Barnet, among his relatives and the scenes of his early childhood; and then proceeded on a visit to the Bishop of Winchester and his old parishioners at Farnham. On his return to town he was seized with an attack of bronchitis, and after six days' illness expired at a quarter past 1 o'clock on the morning of Sunday 20th of February, at the residence of Lady Gipps, the relict of his old friend and schoolfellow the late Governor of New South Wales.

His last hours of consciousness were occupied in pouring forth pious ejaculations, and prayers, and passages of Holy Scripture. Nearly his last words evinced his feelings as a missionary bishop. They were - ' The earth shall be filled with the glory of the Lord.' These words he repeated thrice. After a few more words expressive of humble regret that he should no longer be permitted to be an instrument of furthering that glory, because 'the waters of death had come over him,' he fell peacefully asleep in sure and certain hope of the resurrection to eternal life through Him who is the Bishop and Shepherd of souls. The remains of the first bishop of our Australian colonies lie interred far from the scene of his missionary labours. They were deposited south aisle of Canterbury Cathedral. Annual Register

Notes and Links

1). William Grant Broughton's daughter Mary Phoebe married William Barker Boydell brother of Charles Boydell. They settled at Caergwrle on the Allyn River. Mary Phoebe kept a series of diaries in 1839-18412). William Grant Broughton Correspondence 1833 - 1834 - State Library of New South Wales

3). He visited Sir W. Edward Parry at Port Stephens in June 1831

4). AI created image of a convict ship deck from Rev. Broughton's description

References

(1) K. J. Cable, 'Broughton, William Grant (1788–1853)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University↑